Description

Sensation of environmental cues and decisions made as a result of processing of specific sensory cues underlies a myriad of behavioral responses that control every-day life decisions and ultimately survival in many organisms. Despite the appreciation that organisms can sense, process, and translate sensory cues into a behavioral response, the neural mechanisms and molecules that mediate these behaviors are still unclear. Neurotransmitters, such as glutamate, have been implicated in a variety of sensory-dependent behavioral responses, including olfaction, nociception, mechanosensation, and gustation (Mugnaini et al.., 1984, Wendy et al.., 2013, Daghfous et al.., 2018). Despite understanding the importance of glutamate signaling in sensation and translation of contextual cues on behavior, the molecular mechanisms underlying how glutamatergic transmission influences sensory behavior is not fully understood. The nematode, C. elegans, is able to sense a variety of sensory cues. These types of sensory-dependent behavioral responses are mediated through olfactory, gustatory, mechanosensory and aerotactic circuits of the worm (Lans and Jansen, 2004, Milward et al., 2011, Bretscher et al.., 2011, Kodama-Namba et al.., 2013, Ghosh et al., 2017). Odor guided behavior toward attractants, such as, food cues requires neurotransmitters, that include, glutamate (Chalasani et al.., 2007, Chalasani et al.., 2010). More specifically, once on a food source, wild type N2 hermaphrodites will generally be retained on a food source (Shtonda and Avery, 2006, Milward et al.., 2011, Harris et al.., 2019). The types, quality, pathogenicity, and perception of food can modulate food recognition, food leaving rates, and overall navigational strategies towards food (Zhang et al.., 2005, Shtonda and Avery, 2006; Ollofsson et al.., 2014). These types of behaviors are based on detection of environmental cues, including oxygen, metabolites, pheromones, and odors. Food leaving behaviors have been shown to be influenced by a number of neuronal signals (Shtonda and Avery, 2006, Bendesky et al.., 2011, Ollofsson et al.., 2014, Meisel et al.., 2014, Hao et al.., 2018).

In this present study using our food patch behavioral paradigm, we examined the importance of glutamatergic transmission in the ability of worms to stay on a small food patch. This study has identified a role for glutamatergic transmission in keeping well-fed worms on a small food patch.

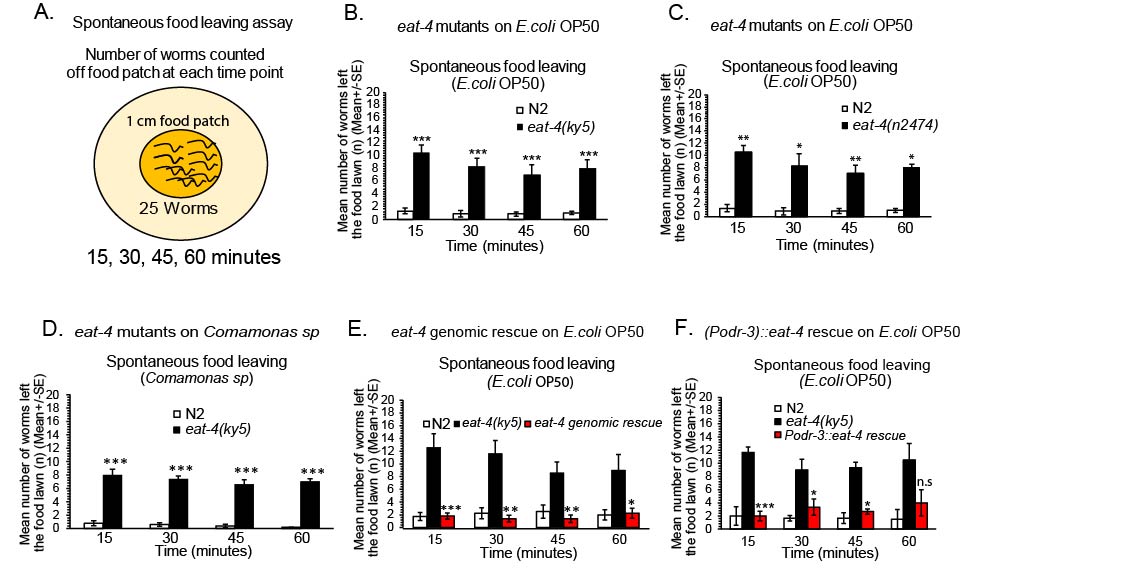

We have examined neurotransmitter systems and their role in the regulation of spontaneous food leaving, while residing on a food patch. Previous studies have implicated molecules in food recognition, dwelling and spontaneous food leaving (Shtonda and Avery, 2006, Bendesky et al.., 2011, Busch and Olloffson, 2012, Olofsson et al., 2014). We first examined wild type N2 food leaving after worms were transferred to a small E.coli OP50 food patch (15, 30, 45 and 60 minutes after transfer to a food patch) (Fig. 1A-1B). Wild type animals generally leave an E.coli OP50 food patch across 0 – 60 minutes infrequently, approximately 3 out of 20-25 worms left an E. coli OP50 food patch across at least the first 1 hour (Fig. 1A, Schematic of behavior assay). We wanted to examine other bacterial food sources in this experiment to assess spontaneous food leaving. We did not choose bacterial species, such as, Pseudomonas aeruginosa (PA14), due to previous studies showing significant food leaving in wild type worms incubated on these types of pathogenic bacteria food lawns over time (Meisel et al.., 2014). We tested wild type N2 worms on an additional food patch, Comamonas sp (Fig. 1D). Wild type animals left with similar rates when compared to E. coli OP50 (Fig. 1B, and 1D). Food leaving rates taken together suggest that wild type N2 worms rarely leave a food patch which agrees with previous appreciation of wild type N2 animals showing low numbers of E. coli OP50 food leaving across the first hour after transfer of wild type N2 worms to a food patch (Harris et al.., 2019). We then sought to investigate the neural mechanisms that mediate staying on a food patch during the first hour.

We examined glutamatergic signaling in this food patch behavior through examination of eat-4 mutants. eat-4 encodes a vesicular glutamate transporter in C. elegans (Lee et al.., 1999). Interestingly, eat-4 mutants were significantly enhanced food leavers (eat-4(ky5) (Fig. 1B, See time course over 60 minutes, Lee et al.., 1999). eat-4(ky5) mutants show a significant increase in the number of worms that were not on the food at time points across 15, 30, 45 and 60 minutes (Fig. 1B). This could be repeated by testing a second allele of eat-4 with significantly reduced function, eat-4(n2474) (Fig. 1C, Lee et al.., 1999). Suggesting, eat-4 removal disrupts normal food patch behavior on an E. coli OP50 food patch. To confirm this phenotype in eat-4 mutants, we examined eat-4 mutants that were rescued with a full-length genomic fragment (Rankin et al.., 2000; Fig. 1E). eat-4 mutants were rescued for food patch behavior (Fig. 1E), confirming that eat-4, and thus glutamatergic signaling is important in this behavior. To examine whether this eat-4-dependent phenotype can be observed on more than one food type, we examined eat-4 mutants on additional food types. We examined eat-4 mutants for their spontaneous food leaving on an Comamonas sp food patch to see if this food type also fails to keep eat-4 mutants on the food patch over 1 hour (Fig. 1D). eat-4 mutants again did show an obvious food leaving phenotype when compared to wild type animals on Comamonas sp food lawns (eat-4(ky5) tested), Fig. 1D). Suggesting, that changing the type of food patch, does not significantly reduce eat-4 mutant-dependent increase in spontaneous food leaving on the food patch (Fig. 1). Therefore, eat-4 mutants fail to stay on multiple types of food, including E. coli OP50 and Comamonas sp. To determine where glutamate signaling is important for keeping worms on a food patch, we examined the site of eat-4 in mediating staying on a food patch. We examined strains that selectively rescue eat-4 in specific sets of glutamatergic neurons. eat-4 is expressed in over 30 neurons in the hermaphrodite, including, sensory and interneurons (Serrano-Saiz et al.., 2013). We examined eat-4 mutants that were rescued using the odr-3 promoter that expresses strongly in the AWC sensory neurons, weakly in the AWB sensory neurons and faintly in the AWA, ASH and ADF sensory neurons (Royaie et al.., 1998, Chalasani et al.., 2007, Calhoun et al.., 2015, Fig. 1F). Interestingly, eat-4 rescue using an odr-3 promoter rescued eat-4(ky5) mutants for staying on a food patch (Fig. 1F). This overall study shows that glutamatergic transmission is important in keeping worms on a food source.

Methods

Request a detailed protocolWorm, media, plate preparation and maintenance. All wild type animals were grown at 20-22 degrees with sufficient E.coli OP50 food source prior to examination of all worms (Brenner et al.,1974). All wild type worms tested in this present study were 1 day old adult hermaphrodite animals under non-starved conditions. To prepare the food lawn used in the assay, NGM-bacterial culture was prepared the night before the assay (40 mL + E.coli OP50 colony) and then 55 µL of the overnight culture was added to the center of a 6 cm NGM plate and left to dry for 2 hours to produce a 1 cm food lawn. After 2 hours, worms were added to the food patch to examine food leaving across the next 60 minutes.

Spontaneous food leaving on E. coli OP50 and Comamonas sp. To determine if glutamate signaling is involved in the present behavior, we measured food leaving as follows: Wild type young adults were added to the relevant food lawn (1 cm diameter, Harris et al.., 2019). The number of worms found off the food were recorded every 15 minutes for 1 hour from the point of adding the worms to the food lawn (0 – 60 minute assay, see Schematic, Fig. 1A). We then compared mutant worms with wild type animals tested in parallel. 3-6 days were performed for each mutant or transgenic rescue lines tested when compared to wild type animals. For data analysis for E.coli OP50 or Comamonas sp food lawns, a student’s t test was performed to compare all mutants vs wild type (N2) animals, or mutant animals vs transgenic rescued animals. Mean ± SEM, Student’s t-test, * p ≤ 0.05, **p ≤ 0.01, ***p ≤ 0.001.

Reagents

Strain list: All strains were purchased from CGC

The following strains were examined in this experiment. MT6308 eat-4(ky5)III, MT6318 eat-4(n2474)III, CX6827 kyEx844 contains [odr-3::eat-4 + elt-2::GFP], DA1242 eat-4(ky5) III; lin-15B&lin-15A(n765)X; adEx1242. E.coli OP50 bacteria was purchased from CGC (Minnesota), Comamonas sp was purchased from CGC (Minnesota). Strains were provided by the CGC (Caenorhabditis Genetics Center), which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

Acknowledgments

We thank biology undergraduate lab members of the Harris lab for reading the manuscript and critical discussion of the data for this experiment. This project was planned and executed by undergraduate researchers under supervision of the principal investigator of the lab(Dr. Gareth Harris). We also thank our Biology program Instructional Support Technicians Catherine Hutchinson and Mike Mahoney for their diligent efforts with reagent ordering and help with other aspects of our lab.

References

Funding

All reagents used for experiments in this study were funded through the PI laboratory startup funds (2017-2020, Dr. Gareth Harris, CSUCI).

Reviewed By

Jagan SrinivasanHistory

Received: August 3, 2020Revision received: November 13, 2020

Accepted: November 17, 2020

Published: November 28, 2020

Copyright

© 2020 by the authors. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Citation

Wolf, T; Perez, A; Harris, G (2020). Glutamatergic transmission regulates locomotory behavior on a food patch in C. elegans. microPublication Biology. 10.17912/micropub.biology.000332.Download: RIS BibTeX