current address: Clem Jones Centre for Ageing Dementia Research, Queensland Brain Institute, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia

Abstract

Strong loss-of-function or null mutants can sometimes lead to a penetrant early lethality, impairing the study of these genes’ function. This is the case for the ceh-6 null mutant, which exhibits 100% penetrant lethality. Here, we describe how we used gene bashing to identify distinct regulatory regions in the ceh-6 locus. This allowed us to generate a ceh-6 null strain that is viable and still displays ceh-6 mutant Y-to-PDA transdifferentiation phenotype. Such strategy can be applied to many other mutants impacting viability.

Description

Loss of the activity of certain genes, such as ceh-6, can lead to lethality at early developmental stages, precluding the study of their function later on during development. Indeed, it was reported that more than 80% of ceh-6(mg60) animals died during embryogenesis exhibiting various phenotypes, including an abnormal rectal area and absent excretory canal cell (Bürglin and Ruvkun 2001). mg60 is a 1.4kb deletion allele that removes ceh-6 second exon and is believed to cause the null phenotype. The expression pattern of ceh-6 is complex and matches the reported defects. Most of the ceh-6 expressing cells, which include head neurons, dividing Pn.a cells in the ventral cord, the excretory cell, and rectal cells, are not related by cell lineage nor by function (Bürglin and Ruvkun 2001).

We have previously shown that knock-down of ceh-6 activity results in a loss of Y cell transdifferentiation (Td) (Kagias et al.. 2012), and that ceh-6 RNAi inactivation at low dsRNA concentration leads to low penetrance Td defects (Kagias et al.. 2012). Since the early lethality associated with strong loss-of-function or null ceh-6 alleles precludes the study of its role during Td, we sought to engineer a viable ceh-6 mutant that lacks ceh-6 activity in the Y cell. One strategy is to drive expression of ceh-6 in the cells where its activity is needed for viability, but not in the cell where it acts to promote Td. However, the cellular focus for the lethality is unknown, precluding a strategy where expression of ceh-6 WT cDNA would be specifically targeted to these cells. Since our previous results suggested that ceh-6 could act cell-autonomously in the Y cell (Kagias et al. 2012), we sought to identify the genomic region(s) within the ceh-6 locus that are necessary for expression in the Y or the rectal cells. Removing these regions from an otherwise ceh-6 rescuing construct should help to generate a viable ceh-6 mutant that lacks ceh-6 expression in the Y or rectal cells. To do so, we have initiated a gene bashing of the ceh-6 locus and have assessed the ability of the fragments to i) rescue the lethality of ceh-6 mutants; and ii) still result in Td defect, correlated with a loss of ceh-6 expression in Y or all rectal cells.

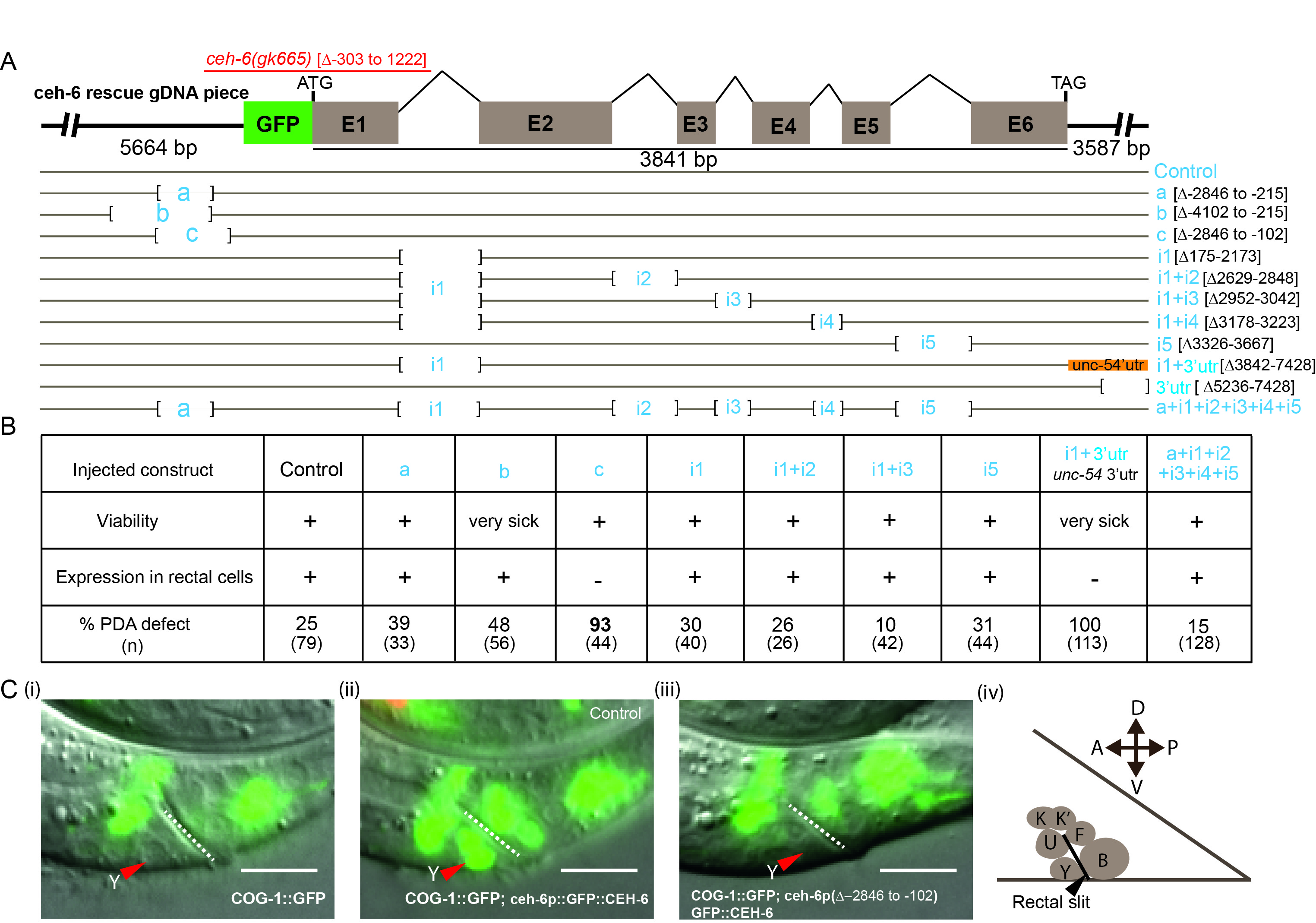

The ceh-6 gene consists of six exons intervened by five introns, spanning a 3.8kb region (https://wormbase.org/species/c_elegans/gene/WBGene00000431#0-9fb-10). A 13kb fragment for the ceh-6 locus that includes 5.6kb of upstream sequences and 3.6kb of downstream sequences was used as a template (Fig.1A, control construct). This fragment is able to rescue the phenotypes of ceh-6(gk665) mutants, including its lethality and Y Td defect (Fig.1B). In this construct, the GFP sequence was fused in frame with the ATG of the ceh-6 gene to follow ceh-6 expression in transgenic animals during rescue experiments (Fig. 1A, C), and we have found it to be expressed in the rectal cells (Fig.1C panel (ii)). A PCR-based approach was used to delete several different regions of the ceh-6 locus (Fig. 1A). We focused on the first intron of the ceh-6 gene, by far the largest, as well as on the upstream region as they contain several conserved sequence elements when compared with other Caenorhabditis species (ceh-6 UCSC browser). In addition, promoter regions and long first introns have been shown to bear different transcription factor binding sites that may act as additive regulatory regions (Fuxman Bass et al. 2013).

Rescue experiments were performed by injecting these constructs in ceh-6(gk665) deletion mutants, which bear a 1.5kb deletion encompassing the first exon and most of the first intron (Bürglin and Ruvkun 2001; The C. elegans Deletion Mutant Consortium 2012) and exhibit defects similar to the mg60 allele, including an early lethality (see Methods). No rescue of ceh-6(gk665) lethality was obtained when ceh-6 3’UTR sequences were altered or when both the first and fourth introns were removed (Fig.1A, constructs ∆3’UTR and I1+I4). In addition, removal of a large upstream region (-4102 to -215, Fig.1A, construct b), or removal of intron 1 plus swapping of ceh-6 3’UTR (Fig.1A, constructI1+u-54 3’UTR) led to poor worm survival. These constructs were not further pursued. Constructs with the simultaneous deletion of two or all five introns (Fig.1A) were able to rescue the lethality, suggesting that these regions are dispensable for expression in the cells where lack of ceh-6 activity causes lethality. However, these constructs still led to expression in the rectal cells and, in large part, rescued the Td defect of ceh-6 null mutants (Fig. 1B). Large deletions in the upstream region (3887bp and 2631bp resp., Fig.1A, constructs a, b) did not affect expression of the construct in rectal cells either and led to significant rescue of the Td defect. Interestingly, eliminating an additional 113bp closer to the ATG (Fig.1A, construct c) resulted in the complete loss of ceh-6 expression exclusively in rectal cells (Fig. 1B, Fig. 1C panel (iii)), while its expression appeared normal in other tissues, like the excretory cell and head neurons. Importantly, while construct “c” successfully rescued the lethality of ceh-6 mutants, transgenic animals exhibited a very penetrant Y Td defect (93%). Thus, most of our constructs rescued ceh-6(gk665) lethality. Two constructs, “c” and “i1+3’utr”, resulted in no visible expression in the rectal cells and a corresponding highly penetrant Y-to-PDA transdifferentiation defect, confirming that ceh-6 activity is necessary in the rectal cells for Y identity swap. Of these two constructs, “c”, which lacks an upstream region, resulted in a relatively healthy transgenic strain.

In summary, we dissected the ceh-6 gene regulatory sequence in the upstream, intronic and 3’UTR regions. We have identified a small regulatory sequence, located upstream and close to the ATG, that is necessary to drive expression in the rectal cells. A deletion encompassing this region allowed us to build a ceh-6 synthetic mutant that can be used as a unique tool to study the rectal-specific function of ceh-6, for example in Y-to-PDA natural transdifferentiation.

Methods

Request a detailed protocolAll strains were cultured using standard conditions (Brenner 1973). The ceh-6 genomic loci, encompassed by fosmid WRM0633dB02, was tagged in-frame at the N-terminus with a GFP as described earlier (Tursun et al. 2009). To create a GFP::ceh-6 rescuing construct, GFP-tagged fosmid WRM0633dB02 was used as a template to PCR-amplify a 13993bp fragment using custom-made oligos (table 1), which encompasses the ceh-6 gene as follows: 5664bp of the ceh-6 upstream region, ceh-6 ORF and 3587bp of the downstream sequence. This 13993bp genomic region was cloned into the pSCB vector using the StrataClone Blunt PCR cloning kit (Agilent Technologies) yielding pSJ6255, which was further used as a parent template to generate all specific deletions as highlighted in Figure 1A. All deletion constructs were made using custom oligos (Table 1) through standard reverse polymerase chain reactions with Phusion® High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (M0530, NEB) and a Bio-Rad T100 Thermocycler. PCR fragments were phosphorylated using T4 Polynucleotide Kinase (M0201, NEB), and religated using T4 DNA Ligase (M0202, NEB). The ceh-6 3’utr was altered by digesting the plasmid with Sph1 and re-ligation on itself.

To generate ceh-6 transgenic lines, the ceh-6 genomic constructs to be tested were injected in IS2581 [ceh-6(gk665) I / hT2[qIs48]; syIs63[cog-1::gfp; unc-119(+)]] animals (5ng/µl), together with a co-injection marker odr-1p::RFP (pSJ6106, 50ng/µl) and pBSK+(200 ng/µl). hT2[qIs48] animals are recessive lethal; we found that homozygotes ceh-6(gk665) animals are 100% lethal before the L2 stage [as such, all growing progeny from ceh-6(gk665) / hT2 mother is heterozygote for ceh-6(gk665): 43/43 adults, 33/33 L4 and 53/53 early L3]. Viability was assessed by scoring transgenic ceh-6(gk665) adult worms in our transgenic lines. Transgenic ceh-6 homozygous animals (L3 and older) were scored for the presence of a PDA neuron using the cog-1p::GFP marker as previously documented (Richard et al. 2011; Zuryn et al. 2014).

Reagents

Table 1:

| Plasmid

(construct name) |

Primer | Strain | Extrachromosomal array | Genotype |

| pSJ6255 | ceh-6pF

ataagaatGCGGCCGCcgtgttgctttagcacttctccatcccttc ceh-6 UTR-R tgatgtgagaagtgaagaggattg |

IS2577 | fpEx902[GFP::ceh-6 locus 13kb; odr-1::rfp] | ceh-6(gk665)I; fpEx902; syIs63[cog-1::gfp;unc-119(+)]IV |

| pSJ6321

(a) |

ceh-6gk769extF

ggtggctagacgagacgcagaaag ceh-6pmidR gcaacacgccataaataatgaaacc |

IS2639 | fpEx940[GFP::ceh-6 13kb locus(Δ-2846 to -215); odr-1::rfp] | ceh-6(gk665)I; fpEx940; syIs63[cog-1::gfp;unc-119(+)] IV |

| pSJ6341

(b) |

ceh-6pmidR2

gccatatcgagtatgaaggatatatc 6gk769extF ggtggctagacgagacgcagaaag |

IS2691 | fpEx958[GFP::ceh-6 13kb locus(Δ-4102 to -215); odr-1::rfp] | ceh-6(gk665)I/hT2[qIs48]; fpEx958; syIs63[cog-1::gfp;unc-119(+)] IV |

| pSJ6342

(c) |

ceh-6pmidR

gcaacacgccataaataatgaaacc ceh-6PROMmF cttttgactactacctcttccttttc |

IS2670 | fpEx955[GFP::ceh-6 13kb locus(Δ-2846 to -102); odr-1::rfp] | ceh-6(gk665)I; fpEx955; syIs63[cog-1::gfp;unc-119(+)]IV |

| pSJ6317

(i1) |

ceh-6intron1-1f

gtgaactgtaactccagatttttg ceh-6intron1-1r ctttatgcctagaaaataacaatctatc |

IS2628 | fpEx938[GFP::ceh-6 13kb locus(Δ175-2173); odr-1::rfp] | ceh-6(gk665)I; fpEx938; syIs63[cog-1::gfp;unc-119(+)]IV |

| pSJ6323

(i1+i2) |

ceh-6exon2f

atacacacaagcagatgtaggtg ceh-6exon2r cctaatttgattcttctctgctta |

IS2648 | fpEx945[GFP::ceh-6 13kb locus (Δ175-2173 & Δ2629-2848); odr-1::rfp] | ceh-6(gk665)I; fpEx945; syIs63[cog-1::gfp;unc-119(+)] IV |

| pSJ6324

(i1+i3) |

ceh-6exon3f

aatatgtgcaaactaaagccac ceh-6exon3r cttgaaagagagttgaagcgcttc |

IS2651 | fpEx948[GFP::ceh-6 13kb locus (Δ175-2173 & Δ2952-3042); odr-1::rfp] | ceh-6(gk665)I; fpEx948; syIs63[cog-1::gfp;unc-119(+)] IV |

| pSJ6319

(i5) |

ceh-6exon4f

gttgtccgtgtctggttctgcaat ceh-6exon4r ctctttctcaagctgcaactccatg |

IS2645 | fpEx944[GFP::ceh-6 13kb locus (Δ3326-3667); odr-1::rfp] | ceh-6(gk665)I; fpEx944; syIs63[cog-1::gfp;unc-119(+)] IV |

| pSJ6318

(i1 + 3’utr unc-54 UTR) |

U54swapF

ctcaacagagcccgagacaacaatagcaactgagcgccggtcgctacc U54swapR cagcgaccaatgtggaattcgcccttaccgtcatcaccgaaacgcgcgagacg |

IS2603 | fpEx930[GFP::ceh-6 13kb locus (Δ175-2173 & Δ 3842-7428

+ unc-54 3’UTR; odr-1::rfp] |

ceh-6(gk665)I; fpEx930; syIs63[cog-1::gfp;unc-119(+)]IV |

| pSJ6355

(a+i1+i2+i3+i4+i5) |

ceh-6gk769extF

ggtggctagacgagacgcagaaag ceh-6pmidR gcaacacgccataaataatgaaacc + ligation to cDNA |

IS2624 | fpEx924[GFP::ceh-6 13kb locus (Δ-2846 to -215 & Δ175-2173 & Δ2629-2848 & Δ2952-3042 & Δ3178-3223 & Δ3326-3667); odr-1::rfp] | ceh-6(gk665)I; fpEx924; syIs63[cog-1::gfp;unc-119(+)]IV |

| pSJ6325

(i1+i4) |

Ceh-6exon4bf

gtcaatgtaaaatctcgtcttg Ceh-6exon4br ctcaatgcttgttctcttctttc |

No lines | ||

| pSJ6322

(3’utr deletion) |

deletion using two Sph1 natives sites | Very sick

No line kept |

||

Acknowledgments

Some strains were provided by the International C. elegans Gene Knockout Consortium and the CGC, which is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440).

References

Funding

This work was funded by an ERC CoG PlastiCell # #648960 to SJ. SJ is a CNRS research director

Reviewed By

AnonymousHistory

Received: October 26, 2020Revision received: December 7, 2020

Accepted: December 15, 2020

Published: December 21, 2020

Copyright

© 2020 by the authors. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Citation

Ahier, A; Suman, SK; Jarriault, S (2020). Gene bashing of ceh-6 locus identifies genomic regions important for ceh-6 rectal cell expression and rescue of its mutant lethality. microPublication Biology. 10.17912/micropub.biology.000339.Download: RIS BibTeX