University of Wisconsin-Madison: Department of Biochemistry, Madison, WI USA

University of Wisconsin-Madison: Department of Medical Genetics, Madison, WI USA

Description

Most eukaryotic genes make nascent transcripts that include both introns and exons. Introns are spliced out, usually co-transcriptionally, to generate mature mRNA (Herzel et al. 2017). Once considered a byproduct of transcription, introns are now known to affect virtually all aspects of mRNA metabolism, from transcriptional initiation to translation (Swinburne and Silver 2008; Chorev and Carmel 2012; Rose 2019). Genes can have multiple introns of variable size, but the first intron is often the longest (Smith 1988; Kriventseva and Gelfand 1999; Bradnam and Korf 2008). We wondered if the long first intron of a critical developmental regulator might affect its expression during development. To address this question, we analyzed expression of the C. elegans mpk-1b RNA, which encodes a nematode ERK/MAPK ortholog and has a long first intron (Figure 1A). Because mpk-1b is a germline-specific RNA (Lee et al. 2007; Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020a), we assayed its expression along the developmental axis of the distal gonad (Figure 1B). Here, germ cells move through three regions as they progress from germline stem cells (GSCs) to differentiation: GSCs and GSC daughters primed for differentiation reside in the Progenitor Zone (PZ); germ cells enter meiotic prophase in the Transition Zone (TZ); and continue through meiotic prophase in the Early Pachytene (EP) region (Figure 1B)(Hubbard and Schedl 2019). Previously, we reported that a set of three ~1 kb deletions at distinct sites within the mpk-1b long intron did not affect its transcription or mRNA abundance (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020b). Here, we report effects of these deletions on production of the MPK-1B protein.

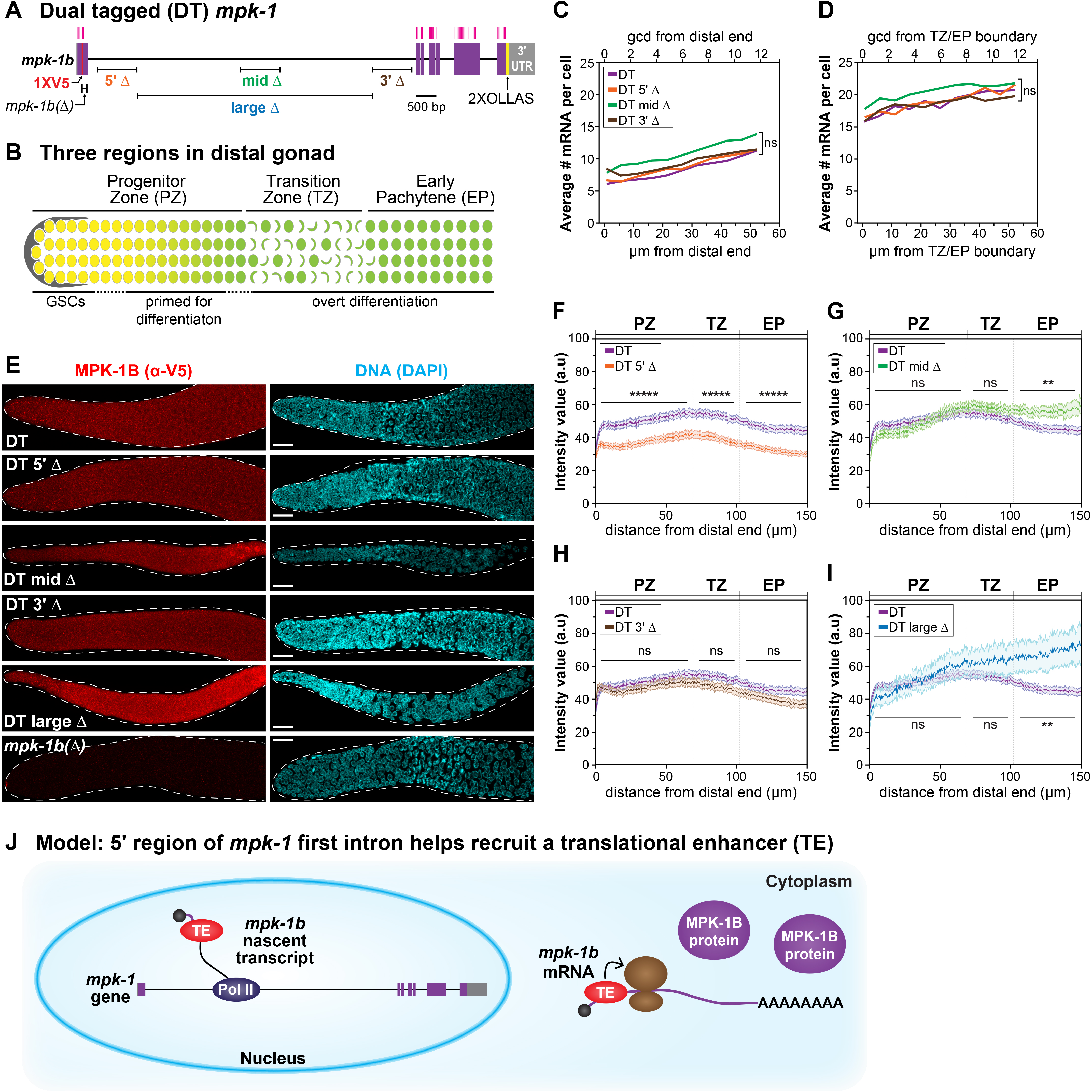

Previously we characterized deletions within the long first intron in an untagged mpk-1 locus (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020b), and in a separate work, we generated an mpk-1 locus with two epitope tags—dual tagged (DT) mpk-1 (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020a). To assay effects of the intron deletions on MPK-1B protein production, we generated them in DT mpk-1. The three smaller deletions are each ~1 kb in length, while a larger deletion is 5.7 kb (Figure 1A). DT 5’Δ removes an in silico-predicted hair pin loop; DT mid Δ removes an enhancer for the somatic mpk-1a transcript; and DT 3’Δ removes a region with no distinguishing features, as described previously (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020b).

First, we asked if the DT deletions affect mpk-1b mRNA abundance. We performed single molecule in situ hybridization (smFISH) in gonads homozygous for each deletion, followed by MATLAB analysis of mRNA abundance as a function of distance along the developmental axis (see Methods) (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020b); the MATLAB code did not allow analysis of DT large Δ (see Methods). For each variant, we scored mRNA abundance in the distal PZ (12 rows from distal end) (Figure 1C) and in the EP (12 rows from TZ/EP boundary) (Figure 1D) and compared results for each DT deletion with the DT mpk-1 control. The mRNA abundance per cell did not differ statistically between any of the intron deletions and the control, as expected from analyses of the same deletions in the untagged mpk-1 locus (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020b). We conclude that mRNA abundance is not affected by the various intron deletions.

Second, we asked if the DT intron deletions affect MPK-1B protein abundance. To this end, we used V5 antibody to detect MPK-1B in the distal gonad (Figure 1B) of DT mpk-1, DT mpk-1b(Δ), and all four DT intron mutants (Figure 1E). Briefly, we quantified MPK-1B fluorescence using ImageJ (see Methods) and normalized intensities to DT mpk-1b(Δ), which does not make MPK-1B (Figure 1E-I). MPK-1B abundance was lower in DT 5’Δ than DT MPK-1B in all three germline regions (Figure 1F), whereas MPK-1B did not differ in DT 3’Δ and the control (Figure 1H). In DT mid Δ and DT large Δ, the MPK-1B abundance was not statistically different from control in the PZ and TZ, but was higher in the EP (Figure 1F, 1J). Because both mid Δ and large Δ remove an enhancer of somatic mpk-1a (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020b), we favor the idea that this EP effect is due to altered somatic MPK-1A activity, and hence is an indirect result of defective feedback on the germline; alternatively, the effect could be direct with the mid Δ and large Δ lowering MPK-1B translation autonomously in the EP region. Additional experiments are required to distinguish between these two possibilities. We conclude that MPK-1B protein abundance is decreased in 5’Δ gonads compared to control. Because mRNA abundance is unaffected in 5’Δ gonads (Figures 1C-D), the simplest conclusion is that the 5’Δ deletion changes translation of the mpk-1b mRNA.

We do not understand how the mpk-1b long first intron enhances translation of the mpk-1b mRNA but note that other examples occur throughout Eukarya (Shaul 2017). The mechanism is also not fully understood for other examples, but one model is that a translational enhancer, perhaps the exon junction complex (EJC), joins the nascent transcript in the nucleus and moves with the mature mRNA to the cytoplasm where it enhances translation (Chazal et al. 2013; Heath et al. 2016; Hir et al. 2016). By analogy, we speculate that a translational enhancer associates with the mpk-1b nascent transcript in the nucleus and moves with mpk-1b mRNA to the cytoplasm where it promotes translation (Figure 1J).

Methods

Request a detailed protocolStrains and growth conditions: All strains were maintained at 20°C on OP50 seeded plates. All strains will be available at the CGC.

| Strain number | Genotype | Shorthand |

| N2 | wildtype | WT (untagged) |

| JK6383 | mpk-1(q1183) III | DT |

| JK6406 | mpk-1(q1204) III | DT 5’Δ |

| JK6404 | mpk-1(q1202) III | DT mid Δ |

| JK6407 | mpk-1(q1208) III | DT 3’Δ |

| JK6452 | mpk-1(q1206) III | DT large Δ |

| JK6403 | mpk-1(q1201) III/qC1[qIs26] III | mpk-1b(Δ)/Balancer |

CRISPR-induced intron deletions in mpk-1DT: All deletions were made using published crRNAs and protocols (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020b).

smFISH, imaging, and MATLAB analysis: Young adult hermaphrodites (L4+12 hr) were dissected and stained with mpk-1 smFISH using both intron and exon probe sets, as previously described (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020a). Because the MATLAB code requires signals from both intron and exon probes, mRNA abundance could not be assessed for DT large Δ, which removes most intron probe binding sites. Individual smFISH exon and intron probe set sequences, smFISH control images, and untagged intron deletion data are published (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020b). After staining, gonads were mounted in Prolong Glass, sealed with VALAP, and stored at -20°C. We used a Leica SP8 confocal microscope and the same imaging conditions previously described (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020b). Images were analyzed in MATLAB using the same procedure and code as originally described (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020b).

MPK-1B staining, imaging, and quantification: Young adult hermaphrodites (L4+12 hr) were dissected and stained as described (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020a). Mouse α-V5 (Bio-Rad), diluted 1:1000, was used for the primary antibody; α-mouse alexa555, diluted 1:1000, was used for the secondary antibody. DAPI (1 µg/mL) was diluted 1:1000. Gonads were mounted in Prolong Glass antifade, sealed with VALAP, and stored at -20°C. Gonads were imaged on a Leica SP8 confocal microscope following published procedure (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020a). Images were imported into ImageJ and the fluorescence quantification followed published protocol (Robinson-Thiewes et al. 2020a). ImageJ data was exported into MATLAB for downstream analyses.

Replicates: Two replicates were performed for each genotype and each experiment reported. Replicates were raised in parallel on separate plates. For each experiment, replicates were dissected, stained, and imaged in parallel. Because data from the replicates were not statistically significant from each other, they were combined for presentation.

· smFISH in PZ: DT replicate 1, 14; DT replicate 2, 14; DT 5’Δ replicate 1, 20; DT 5’Δ replicate 2, 19; DT mid Δ replicate 1, 15; DT mid Δ replicate 2, 14; DT 3’Δ replicate 1, 19; DT 3’Δ replicate 2, 20.

· smFISH in EP: DT replicate 1, 13; DT replicate 2, 14; DT 5’Δ replicate 1, 18; DT 5’Δ replicate 2, 19; DT mid Δ replicate 1, 15; DT mid Δ replicate 2, 14; DT 3’Δ replicate 1, 19; DT 3’Δ replicate 2, 20.

· Immunostaining: DT replicate 1, 23; DT replicate 2, 24; DT 5’Δ replicate 1, 19; DT 5’Δ replicate 8, 19; DT mid Δ replicate 1, 20; DT mid Δ replicate 2, 6; DT 3’Δ replicate 1, 18; DT 3’Δ replicate 2, 18; DT large Δ replicate 1, 9; DT large Δ replicate 2, 7.

MATLAB analyses: smFISH images were analyzed using codes available at https://github.com/robinson-thiewes/Robinson-thiewes-PNAS-codes- (DOI: 10.5281/zenodo.4007918). All statistical tests used in this work were performed in MATLAB using the student’s t-test ttest2 function. Shaded bar graphs in Figure 1F-I were generated using shadedErrorBar (https://github.com/raacampbell/shadedErrorBar).

Acknowledgments

We thank members of the Kimble and Wickens labs for support and discussion.

References

Funding

S-RT was supported by the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship under grant DGE-1256259 and NIH Predoctoral Training Grant in Genetics 5T32GM007133. JK was an HHMI Investigator and is now supported by the NIH Grant R01 GM134119. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.

Reviewed By

AnonymousHistory

Received: December 15, 2020Revision received: December 29, 2020

Accepted: January 5, 2021

Published: January 14, 2021

Copyright

© 2021 by the authors. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.Citation

Robinson-Thiewes, S; Kimble, J (2021). C. elegans mpk-1b long first intron enhances MPK-1B protein expression. microPublication Biology. 10.17912/micropub.biology.000350.Download: RIS BibTeX